Ischemic cerebral lacunae - lacunar infarcts

Last edited on : 24/09/2024

A cerebral lacuna is defined anatomo-pathologically as a cavity less than 15 mm in diameter (some authors use a different cut-off), located in deep cerebral parenchyma and vascularized by an intracerebral perforating artery (basal ganglia, thalamus, semi-oval center, brainstem). Ischemic cerebral lacunae, or lacunar infarcts, reflect necrosis secondary to a critical lack of oxygen supply, representing a particular form of ischemic stroke.

More rarely, cerebral lacunae may be hemorrhagic, although they classically reflect the same type of micro-angiopathy as ischemic lacunae, or may be confused with dilatations of perivascular spaces, with no proven pathological significance.

In clinical practice, their diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical arguments and, today, decisively on magnetic resonance imaging.

Anatomical and pathological classifications

Classically, three histological types of cerebral lacunae are distinguished:

- Lacunar infarcts - these account for 25% of ischemic strokes.

- They make up the majority of cerebral lacunae, and are observed in 6 to 11% of autopsies (but over 80% of lesions were deemed asymptomatic).

- They result from occlusion of a perforating artery (diameter less than 400 μm, terminal, non-anastomosing: lenticulostriate from the anterior and middle cerebral arteries, thalamo-perforating from the posterior cerebral arteries, paramedian from the basilar trunk).

- Main causes: atherosclerosis of the artery giving rise to the perforating artery, lipohyalinosis.

- Hemorrhagic lacunae (hemosiderin in macrophages, indicating a history of hemorrhage)

- Their radiological differentiation from ischemic lacunae is not always obvious. If necessary, T2* sequences on cerebral magnetic resonance imaging can be used to highlight hemosiderin deposits.

- Virchow-Robin dilatations of the perivascular spaces

- Rounded, regular, frequently containing segments of normal arteries. They are sometimes difficult to differentiate from ischemic or hemorrhagic lacunae, their correct diagnosis depending mainly on the radiologist's degree of expertise.

- Their origin and clinical significance are controversial, with most practitioners currently regarding them as anatomical variants with no pathological character. In any case, since their isolated discovery has no therapeutic implications, their place in this classification is debatable.

Many authors, however, reserve the term lacunae for lacunar infarcts, referring to "hemorrhagic lacunae" as microhemorrhages (or microbleeds). In any case, lacunar infarcts and microbleeds frequently represent two sides of the same micro-angiopathic syndrome.

Elements of pathophysiology

Cerebral lacunae are a manifestation of localized or diffuse microangiopathies. For a long time, in addition to the classic cardiovascular risk factors, a number of factors (systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, haemostasis disorders, etc.), whose pathogenic roles are clearly established, have been suspected of playing a more decisive role than in strokes resulting from macro-angiopathies. At present, however, no significant difference has been demonstrated in this respect.

Aetiologies and risk factors

Risk factors (smoking, alcoholism, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, age, hyperlipidemia) and etiologies (see corresponding chapters) are the same as for non-lacunar stroke. However, the predominance of etiologies differs.

Lipohyalinosis of perforating arteries (clearly the predominant cause)

Arterial lipohyalinosis corresponds to thickening of the vascular wall by a hyaline, lipidic substance and fibrinoid necrosis → loss of vascular parietal architecture. As its frequency is inversely proportional to arterial caliber, it is fairly specific to lacunar infarcts. Its pathogenesis remains debated (altered autoregulation to pressure variations on chronic vasoconstriction secondary to chronic hypertension? Genetic susceptibility? Inflammatory mechanisms? Others).

The risk factors are the same as for all vasculopathies, but the relative risk is significantly higher for arterial hypertension and diabetes.

Cerebral amyloid angiopathies

Cerebral amyloid angiopathies are a heterogeneous group of angiopathies characterized by the presence of amyloid protein deposits in cerebral vessel walls. They are common in elderly patients, and contribute to both cerebral ischemia and hemorrhage.

Atheromatosis and atherosclerosis

The formation of stenosing lesions on atheromatous plaques, involving the classic cardiovascular risk factors, also affects perforators and is thought to be the second most common cause of lacunar infarctions.

As sclerosis phenomena do not affect arteries of the caliber of cerebral perforators, they are only involved in lacunar infarctions resulting from occlusion of the perforators' connection to larger caliber arteries.

CADASIL

Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder (mutation of the Notch 3 gene, chromosome 19) affecting small arteries.

Clinical features: migraines with aura, iterative ischemic strokes (2/3 lacunar syndromes), mood disorders, late-onset dementia. There is no specific therapeutic management.

Other genetic disorders

Other exceptional genetic diseases have been implicated in the genesis of multiple lacunar infarcts: CARASIL (Cerebral Autosomal Recessive Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy), Biswanger-like,...

Various

Other causes (Cf. etiologies of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke) such as microemboli, coagulopathies, infectious or non-infectious vasculitis, etc. have also been reported.

Acute-phase clinic

The majority of infarcts and lacunar haemorrhages are silent, although their accumulation can result in progressive cognitive deterioration, or even the development of a multi-lacunar state (see evolution). When they occur symptomatically, their diagnosis by definition presupposes the absence of cortical signs, and certain pictures are classically described as being more frequent than in other types of stroke, and referred to as "lacunar syndromes", even though they are not pathognomonic:

- Pure motor hemiplegia or hemiparesis

- The most frequent. In most cases affecting at least the lower limb and the upper limb, or one limb and the face.

- Involves the internal capsule in 2/3 of cases. Others: protuberance, corona radiata, cerebellar peduncles, bulb.

- Sensory-motor hemideficit

- Not classically associated with lacunar syndromes, advances in imaging have demonstrated that this is the second most common syndrome. Regions concerned in decreasing order of frequency: posterior arm of the internal capsule, corona radiata, knee of the internal capsule, thalamus, anterior arm of the internal capsule.

- Pure sensory hemideficit

- Rare (may be underdiagnosed due to isolated sensory disturbances, not very suggestive), generally reflecting very small infarcts.

- Ataxic hemiparesis

- Includes two "classic" syndromes: "homolateral crural ataxia and paresis" and "dysarthria - clumsy hand".

- They usually involve protuberant lesions.

- Capsular warning syndrome

- "Capsular warning syndrome" is a particular form of transient ischemic attack (TIA), characterized by the repetition at short intervals of identical hemicorporeal motor or sensory-motor deficits of brief duration. Progression frequently leads to an infarct in the capsulostriate region, exceptionally in the brainstem.

- Various presentations are rare to exceptional, although sometimes highly suggestive (e.g. the sudden and isolated appearance of involuntary hemichorea or hemiballism movements in a patient with cardiovascular risk factors, frequently mistaken for partial epileptic seizures in emergency departments).

Evolution

Short-term mortality is low (2% versus 10-20% for non-lacunar infarcts at 1 month, 8% versus 20% at 1 year) and 5-year mortality 25% (essentially due to cardiac pathologies of the same pathophysiology).

The functional prognosis is also better, with the exception of cognitive impairment, and the risk of recurrence is lower in the short term (0 to 4% within 1 month versus 5% for non-lacunar infarcts, 5 to 8% versus 10% at 1 year) but similar over the longer term.

Their accumulation rarely results in severe motor deficits, but frequently in the development or worsening of cognitive disorders (11% vascular or mixed dementia at 2 years, 15% at 9 years) or even a "multi-lacunar state" (cognitive disorders, gait disorders often of the praxis type [= astasia-abasia], frontal signs, pseudo-bulbar syndrome).

Their presence is also correlated with an increased risk of intra-parenchymal hemorrhage (IPH), ++ deep and brainstem, which can sometimes even predominate on the ischemic side of the disease.

Additional tests

The additional work-up is that of an ischemic stroke.

Radiological specificities

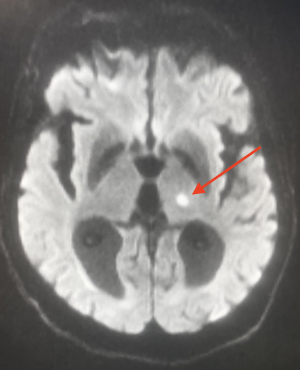

On cerebral CT scans, lacunae may not appear or may appear as oval hypodensities < 15 mm in diameter.

MRI remains the reference examination and can reveal :

- old lacunae: hyper in T2, hypo in T1. Difficult to differentiate from Virchow-Robin perivascular spaces (in the latter case, the lesion is rounder with more regular margins. Topography sometimes helps) even for experienced examiners.

- Recent lacunae: T2 and FLAIR hyper.

- Acute stage: same diffusion and ADC abnormalities as for other types of stroke (hyper in diffusion and hypo in ADC for an infarct).

- Coexistence with other abnormalities:

- Probably related to the same mechanisms. Ex: evidence of micro-bleeds (T2* sequences) or vascular leukopathy (iso-dense areas on CT-scan, hyperintense on T2 and FLAIR).

- Relating to other mechanisms. E.g.: cortical macrobleeds and microbleeds frequently coexist with amyloid angiopathy.

Therapeutic management - Treatments

Recommendations for treatment are similar to those for other types of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (see corresponding chapters). However, we would like to make a few specific remarks concerning ischemic lacunae:

In the acute setting, the benefit and risks (secondary hemorrhage) of IV thrombolysis (although making less sense theoretically) have not been shown to differ from those of other ischemic strokes. Until such time as new data become available, the lacunar nature of an infarct should not, therefore, lead to a patient being rejected for thrombolysis. We can only give special attention to these cases.

In contrast to other ischemic strokes, double anti-platelet aggregation has been shown to significantly increase long-term mortality, and should be avoided as a rule. Single-agent platelet anti-aggregation, on the other hand, has been shown to reduce overall morbidity and mortality (to be weighed against the risk of the possible hemorrhagic side of the disease). We can therefore only recommend prescribing an anti-platelet agent (e.g. acetylsalicylic acid 160 mg/day) on a case-by-case basis.

It should also be noted that in the majority of cases, micro-angiopathy affects other organs, particularly the retina and kidney, and/or is associated with macro-angiopathy.

Bibliography

Arboix A et al., Clinical characteristics of acute lacunar stroke in young adults, Expert Rev Neurother, 2015

Benavente OR et al., Clinical-MRI correlations in a multiethnic cohort with recent lacunar stroke: the SPS3 trial, Int J Stroke, 2014 Dec;9(8):1057-64

Caplan RL, Caplan's Stroke. A clinical approach, 4th ed, Saunders, 2009

Dhamoon MS et al., Long-term disability after lacunar stroke: secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes, Neurology, 2015 Mar 10;84(10):1002-8

Jauch EC et al., Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, Stroke, 2013 Mar, 44(3):870-947

Kwok CS et al., Efficacy of antiplatelet therapy in secondary prevention following lacunar stroke: pooled analysis of randomized trials, Stroke, 2015 Apr;46(4):1014-23

Latchaw RE et al., Recommendations for Imaging of Acute Ischemic Stroke. A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association, Stroke, 2009, 40:3646-3678

Meschia JF et al., Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, Stroke, 2014 Dec, 45(12):3754-832

Mok V et al., Prevention and Management of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease, J Stroke, 2015 May;17(2):111-22

Osborn AG, Diagnostic imaging : brain, Amirsys, USA, 2d ed., 2009

Sharma M et al., Predictors of mortality in patients with lacunar stroke in the secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes trial, Stroke, 2014 Oct;45(10):2989-94

Valdés Hernández MD et al., A comparison of location of acute symptomatic vs. 'silent' small vessel lesions, Int J Stroke, 2015 Jun 29

Wiseman S et al., Blood markers of coagulation, fibrinolysis, endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in lacunar stroke versus non-lacunar stroke and non-stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis, Cerebrovasc Dis, 2014;37(1):64-75

Yoshimura S et al., Cerebral Small-Vessel Disease in Neuro-Behçet Disease, J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2015 Jun 26