Frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis)

Adhesive capsulitis or "frozen shoulder" is defined as the progressive development of joint limitation ("stiffness"), both active and passive, and of shoulder pain with no other explanation. The term "peri-arthritis" is confusing and tends to be abandoned. It is a diagnosis of exclusion made on an essentially clinical basis.

It affects 2 to 5% of the population in the course of their lives, with a slight female predominance. It is rare before the age of 40, with peak incidence in the 50s.

Etiopathogenesis

Adhesive capsulitis is generally idiopathic, or "primary". However, a number of factors have been identified as contributing to the disease:

- Diabetes (10-20% of diabetics will be affected)

- Dysthyroidism (++ hypothyroidism)

- Dyslipidemia

- Autoimmune pathologies

- Prolonged immobilization

Less frequently, it may be secondary to joint trauma (rotator cuff tears, proximal humeral fractures, orthopedic shoulder surgery, glenohumeral subluxations) or muscle spasticity (e.g. following stroke).

Despite various hypotheses, its pathophysiology is still unknown, and even its course is debated (initial inflammatory process? initial fibrosing process? overlap with complex regional syndrome?).

Clinic and prognosis

The diagnosis is based on the clinical features, which are generally stereotyped and characteristic. Three clinical phases can be distinguished:

- Painful phase (duration ++ 2 to 9 months): progressive development of moderate then severe pain, incapacitating joint movement in +- all directions. Pain is initially centred on the joint, but rapidly develops into pain that may be localized to the anterior or lateral aspects of the arm, depending on movement. Nocturnal pain, which may awaken the patient, is common. Stiffness" (joint limitations not due solely to pain) develops in the background.

- Stiff phase (duration ++ 4 to 12 months): pain persists but diminishes, and "stiffness" (joint limitations) comes to the fore.

- Recovery phase (duration ++ 5 to 24 months): disappearance of pain and gradual recovery of joint amplitude.

On examination, there should be active and passive limitation of joint amplitudes in at least two planes (++ external rotation and abduction) compared with the normal shoulder. Pain is typically absent or unobtrusive during isometric efforts (against resistance).

Although long-lasting and incapacitating, the condition is considered benign, as recovery is generally complete in the long term, even without treatment. However, some series suggest that 40% of patients still present symptoms at 3 years, and 10% over the long term.

For some unknown reason, Adhesive capsulitis can only affect the same shoulder once in a lifetime. There is therefore no risk of recurrence. However, the risk of subsequent capsulitis of the contralateral shoulder is slightly increased.

Differential diagnosis

The main confounding diagnoses are subacromial pathologies such as rotator cuff tendinopathies. Clinical evidence is generally sufficient to rule them out (the main difference being the preservation of amplitudes during passive movements in subacromial pathologies).

Investigations

Positive diagnosis is based exclusively on anamnesis and clinical examination. As a rule, no further investigations are necessary, but they may be justified to exclude other pathologies in cases of clinical doubt. By definition, they should not show any other abnormality likely to explain the clinical picture. However, X-rays and/or ultrasound of the shoulder are generally performed.

X-rays usually show no abnormality except for possible osteopenia. Ultrasound may show slight effusion of the long biceps tendon and/or discrete thickening of the caracohumeral ligament and soft tissues of the rotator cuff. MRI may also directly demonstrate thickening of the joint capsule.

Treatments - therapeutic management

Resolution of the pathology is spontaneous, although it seems that some patients will retain joint limitations. Treatments, whose usefulness is based on weak EBM, aim to reduce pain and accelerate recovery.

The treatments generally administered are :

- General advice: as far as possible, maintain pain-free activity. Excessive "resting" of the joint tends to increase short-term pain and delay functional recovery.

- Radiation-guided intra-articular injections of glucocorticoids (e.g. depo-medrol 80 mg) should be given as early as possible. Alleviates pain and significantly accelerates recovery. May be repeated if effective (symptomatology relieved), but symptomatology subsequently recurs.

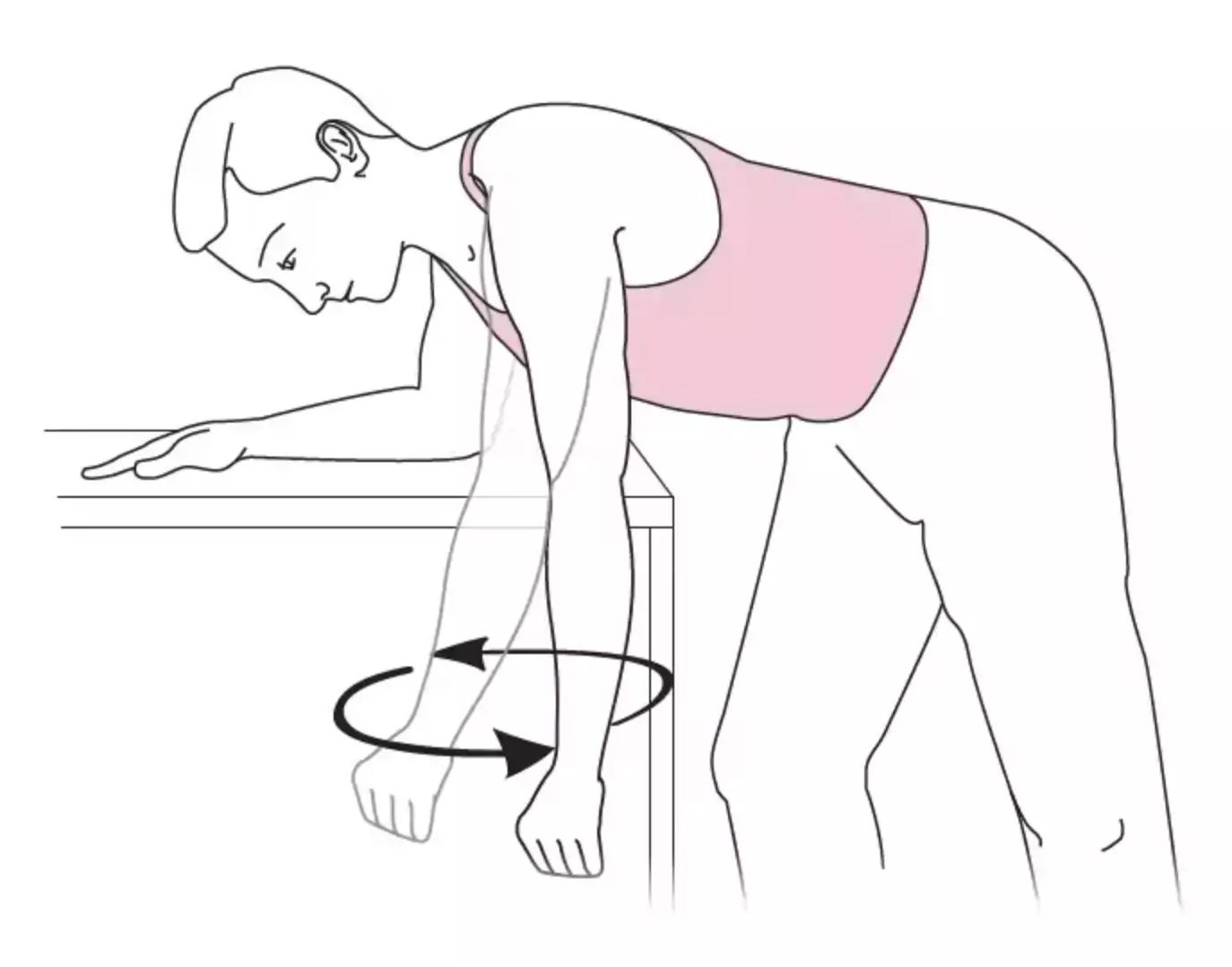

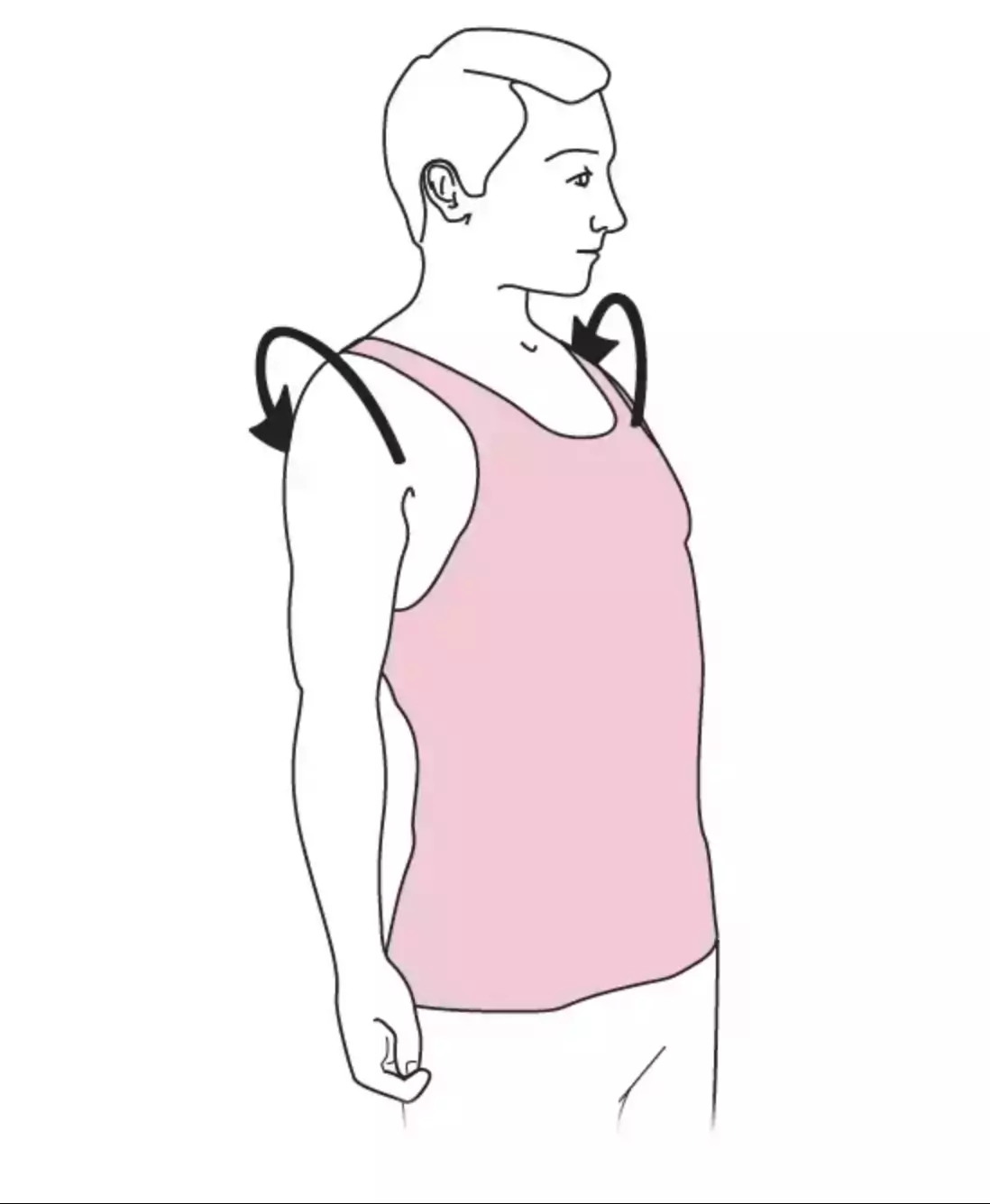

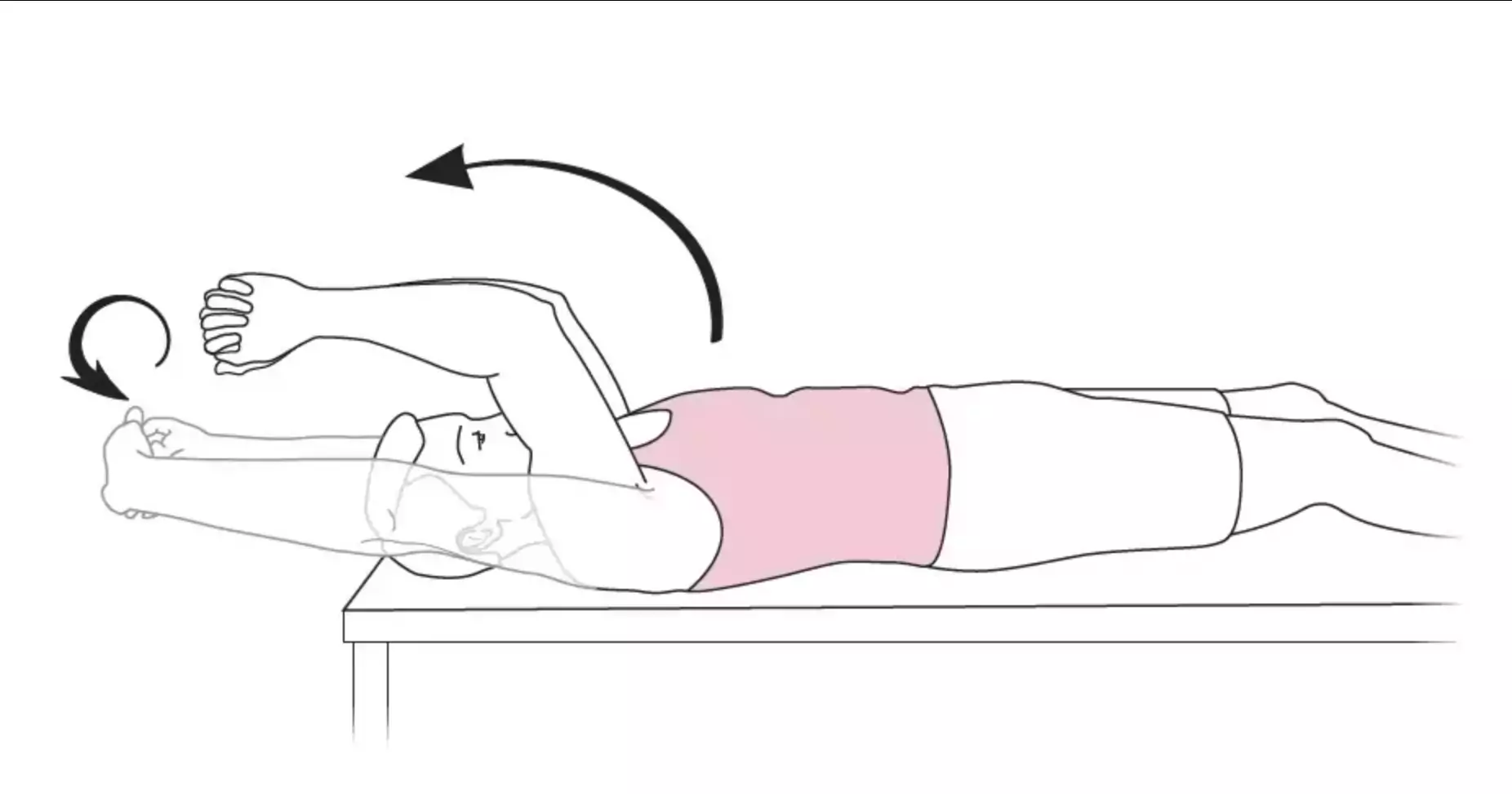

- Physical therapy :

- Physiotherapy 1 to 2x/week

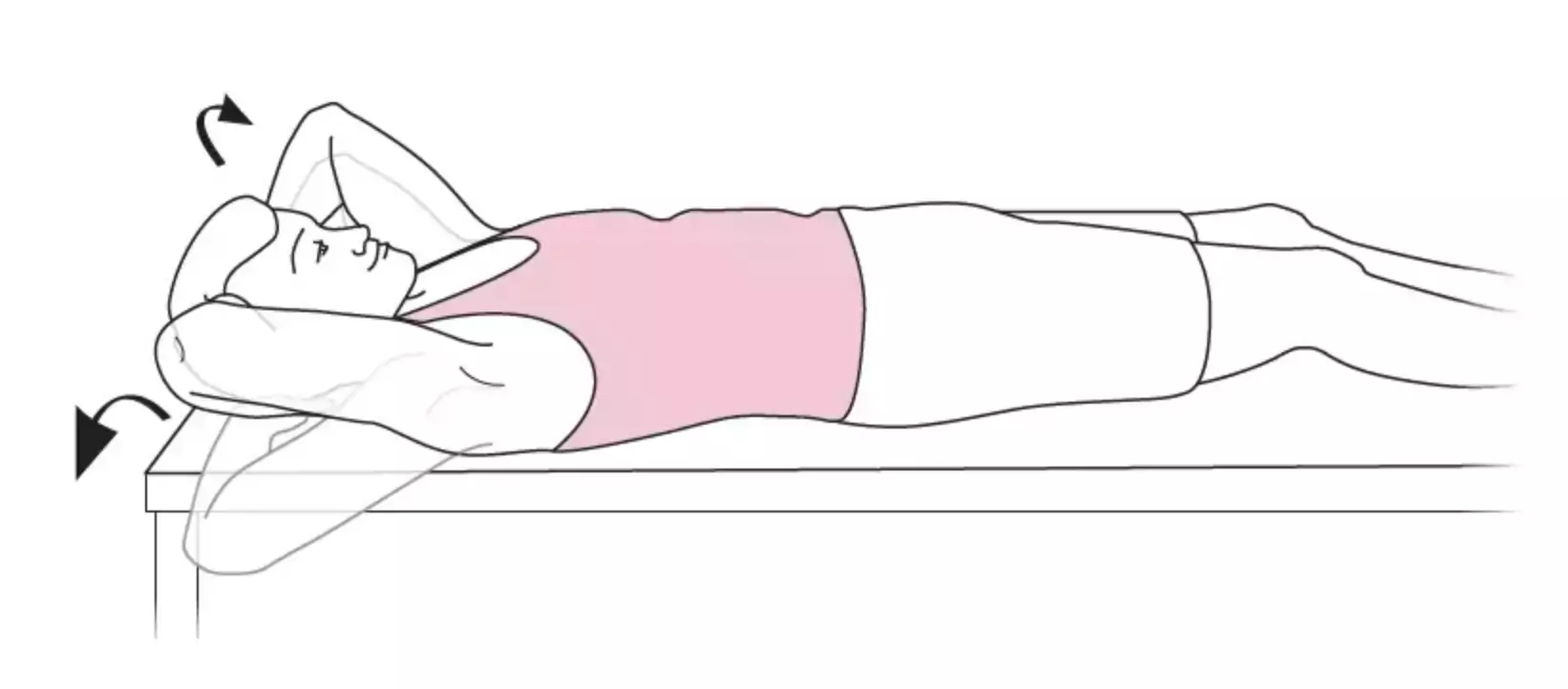

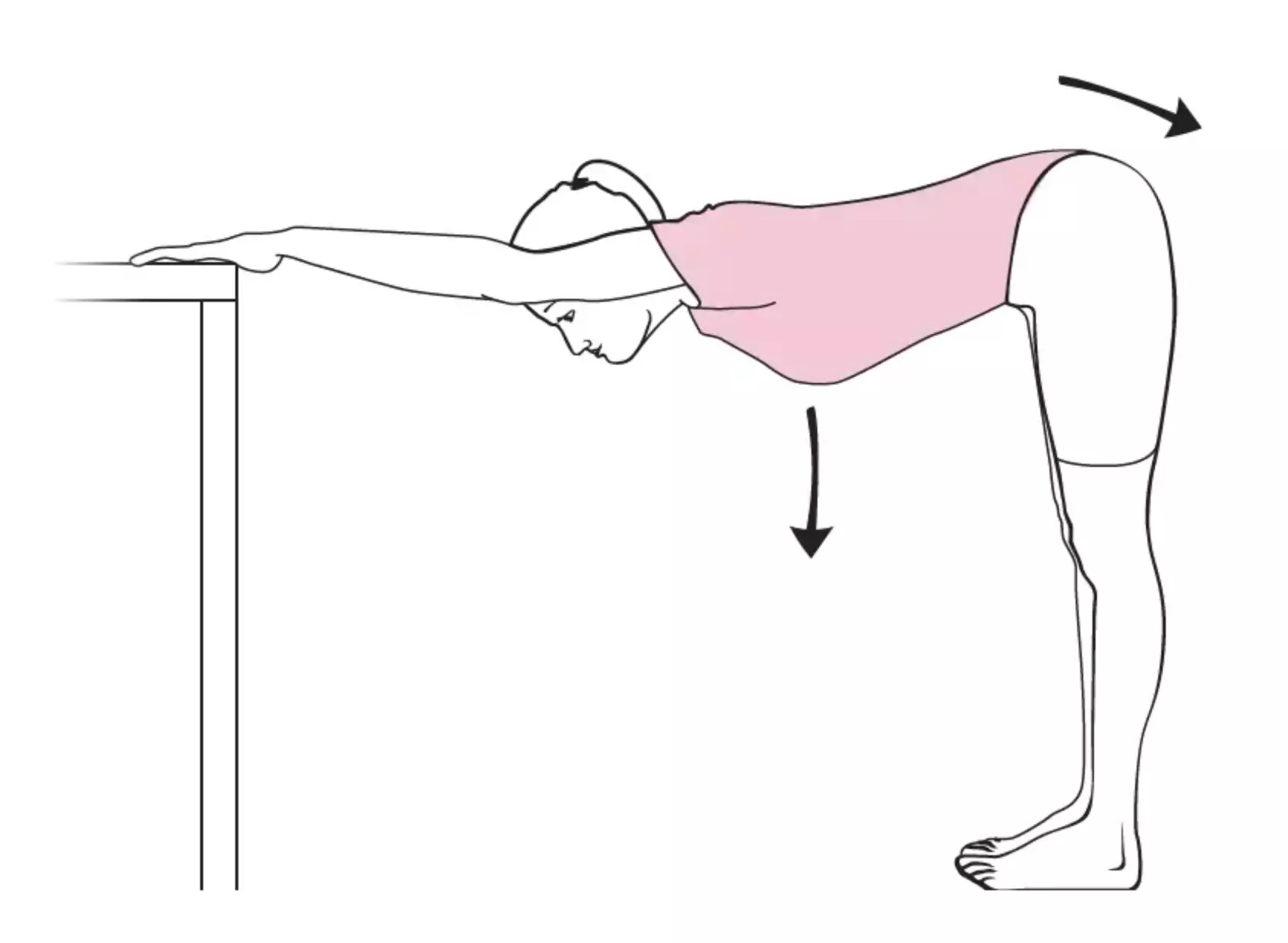

- To be performed by the patient himself: 3 to 6x/ day, do not "force" (stop movement as soon as discomfort appears), provide patient with diagrams

Oral corticosteroids and surgery have shown no benefit in the management of this condition. In exceptional cases, surgery may be considered by an orthopedic surgeon if there is no response to conservative treatment in the medium-to-long term.

Author(s)

Dr Shanan Khairi, MD

Bibliography

Prestgaard TA, Frozen shoulder, Uptodate, 2022

Rangan A et al, Management of adult with primary frozen shoulder in secondary care: a multicentre, pragmatic, three-arm, superiority randomised clinical trial, Lancet, 2020, 396:977